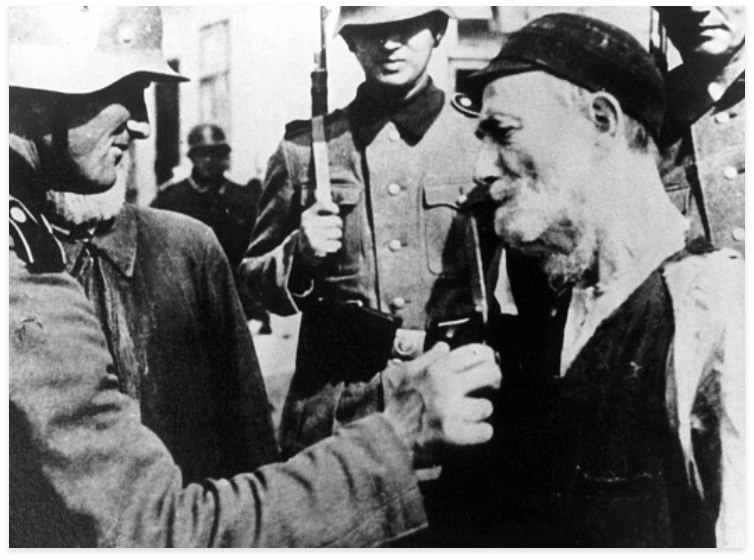

As Hitler advanced, Rosie was still in Hungary, but she heard of what was happening to her family at home. German soldiers were entering homes, cutting the beards of the Jewish men with scissors, and then killing them.

In one situation Rosie's mother hid her father behind a refrigerator to keep him safe. But, that safety was short-lived.